The naming of Montana’s 56 counties

adds color and meaning to our rich heritage

Text by Michael Ober

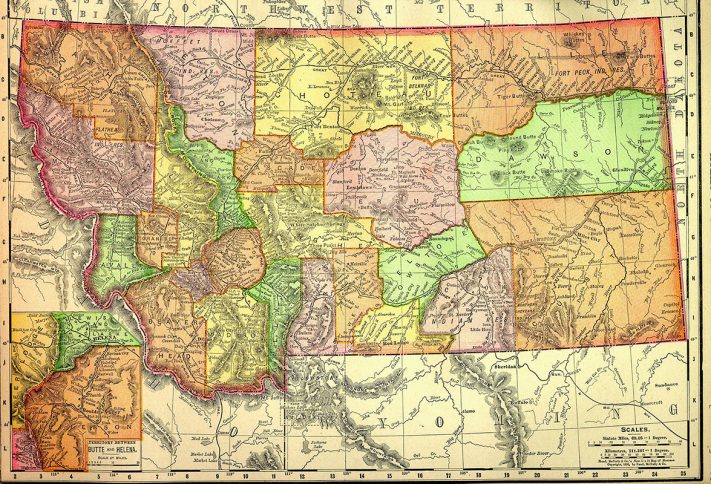

Just how did Montana end up with such a patchwork of unique counties? Examination of historic maps reveals the inexorable expansion of humanity across the territory and, later the state. The peopling and populating of Montana can be told in the origins of its counties.

In its early territorial days, Montana’s population centers were in southwest Montana, clustered around the gold mining boom camps. These “prospector” counties were the first nine counties, carved out chiefly to align with corresponding mining districts. By contrast, the vast “homesteader” counties emerged when eager farmers poured into central and eastern Montana during the nineteen-teens.

In its early territorial days, Montana’s population centers were in southwest Montana, clustered around the gold mining boom camps. These “prospector” counties were the first nine counties, carved out chiefly to align with corresponding mining districts. By contrast, the vast “homesteader” counties emerged when eager farmers poured into central and eastern Montana during the nineteen-teens.

The late historian Dave Walters explains it this way: “The earliest counties, smaller in size, were in the southwest, where the mining centers were and the really big ones were in the eastern part of the state…and nobody’s out there.” That would all change with the Homesteading Era and the great “county-splitting” boom. The thousands of homesteaders who arrived in the nineteen teens brought with them a demand for local county seats of government that were aimed at addressing their agrarian needs: sutler-like towns with sturdy brick banks, implement and hardware stores and grain elevators. The rapid expansion of counties added during the Homesteading Era, 1910-1925, was twenty two.

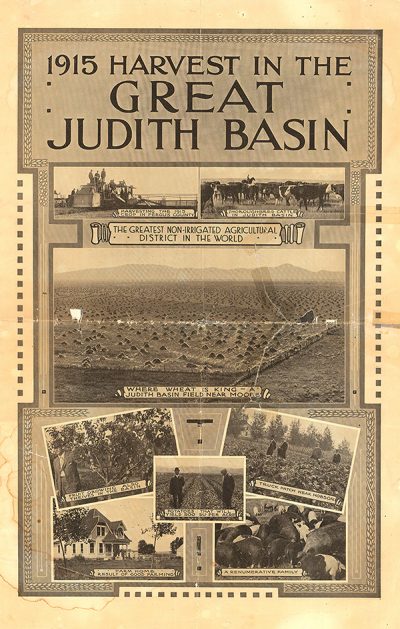

The 1909 Enlarged Homestead Act figured heavily in all this. Hardy homesteaders, bent on prosperity and quick riches from seed crops, anointed their balkanized counties with hopeful names like Treasure, Golden Valley and Wheatland. They divided large counties into smaller ones in a frenzied pace. It made more sense to them to have a county seat 60 miles away instead of 260 miles away, and, so, small towns that formerly had little claim to anything became the central place for farmers to file for deeds, register brands or automobiles, obtain titles to land, secure marriage licenses or start a county school. County seats, then, became magnet communities where folks gathered for the county fair or rodeo or election speeches. Farmers organized their calendars around events like spelling bees, the annual circus, baseball games and threshing contests. To a homesteader, going to town usually meant combining business and trading matters with social activities. You had arrived in social hierarchy if you had your own localized county and county seat with its governmental outlets like a county attorney or county superintendent of schools. It meant solvency. And hope.

The 1909 Enlarged Homestead Act figured heavily in all this. Hardy homesteaders, bent on prosperity and quick riches from seed crops, anointed their balkanized counties with hopeful names like Treasure, Golden Valley and Wheatland. They divided large counties into smaller ones in a frenzied pace. It made more sense to them to have a county seat 60 miles away instead of 260 miles away, and, so, small towns that formerly had little claim to anything became the central place for farmers to file for deeds, register brands or automobiles, obtain titles to land, secure marriage licenses or start a county school. County seats, then, became magnet communities where folks gathered for the county fair or rodeo or election speeches. Farmers organized their calendars around events like spelling bees, the annual circus, baseball games and threshing contests. To a homesteader, going to town usually meant combining business and trading matters with social activities. You had arrived in social hierarchy if you had your own localized county and county seat with its governmental outlets like a county attorney or county superintendent of schools. It meant solvency. And hope.

But when the homesteaders emptied out of Montana in the drought-plagued “bust” of the 1920s, Golden Valley County wasn’t so golden anymore and Richland County no longer delivered bountiful riches. Montana was the only state to lose population in the 1920s. What was left was the jig saw puzzle map of a state that, without citizens, was hard-pressed to support the infrastructure of so many county seats of local governments. But, they stuck anyway.

But when the homesteaders emptied out of Montana in the drought-plagued “bust” of the 1920s, Golden Valley County wasn’t so golden anymore and Richland County no longer delivered bountiful riches. Montana was the only state to lose population in the 1920s. What was left was the jig saw puzzle map of a state that, without citizens, was hard-pressed to support the infrastructure of so many county seats of local governments. But, they stuck anyway.

Thirteen Montana counties are named because of their connection with geographic features, twelve of them for rivers that flow through them. Twenty-six counties are named for men. No Montana county is named for a woman except Judith Basin, but few Montanans could tell you who Judith really was, much less that she was never in Montana. SPOILER ALERT: Captain William Clark named it for his future wife, Julia (Judith) Hancock back home in Virginia. Among the white male names, many of them are for folks who have never even been to Montana like Madison, Jefferson and Gallatin along with Lincoln and Garfield. Alternatively, colorful Montana personages with direct links to the state’s history are spread across the map to lay claim to their Montana reputations, think: Meagher, Custer, Sanders and Lewis and Clark. Even though Montana has seven Indian reservations, there is only one county named for any Montana-related Indian tribe (Flathead), unless you count Pondera, a marginal attempt to connect that tribe to Montana’s history and, even then, the spelling owes little to the original French name of Pend d’Orielle. Teton County also comes close with reference to the Teton Sioux, the westernmost branch of Dakota Siouan cultures, but etymology is often corrupted with the claim, probably apocryphal, that French-Canadian fur traders used the term “teton” for twin mountain peaks on the Rocky Mountain Front resembling breasts. A. B. Guthrie, Jr. tapped into that fanciful notion in his Big Sky epic when he placed Boone and Teal Eye, his central characters, on the Teton River.

Thirteen Montana counties are named because of their connection with geographic features, twelve of them for rivers that flow through them. Twenty-six counties are named for men. No Montana county is named for a woman except Judith Basin, but few Montanans could tell you who Judith really was, much less that she was never in Montana. SPOILER ALERT: Captain William Clark named it for his future wife, Julia (Judith) Hancock back home in Virginia. Among the white male names, many of them are for folks who have never even been to Montana like Madison, Jefferson and Gallatin along with Lincoln and Garfield. Alternatively, colorful Montana personages with direct links to the state’s history are spread across the map to lay claim to their Montana reputations, think: Meagher, Custer, Sanders and Lewis and Clark. Even though Montana has seven Indian reservations, there is only one county named for any Montana-related Indian tribe (Flathead), unless you count Pondera, a marginal attempt to connect that tribe to Montana’s history and, even then, the spelling owes little to the original French name of Pend d’Orielle. Teton County also comes close with reference to the Teton Sioux, the westernmost branch of Dakota Siouan cultures, but etymology is often corrupted with the claim, probably apocryphal, that French-Canadian fur traders used the term “teton” for twin mountain peaks on the Rocky Mountain Front resembling breasts. A. B. Guthrie, Jr. tapped into that fanciful notion in his Big Sky epic when he placed Boone and Teal Eye, his central characters, on the Teton River.

With a nod to resource wealth, there’s Carbon County, Treasure County, Mineral County and Petroleum County. Some of the personal names are associated with a Catholic missionary (father Anthony Ravalli), cattle barons (James Fergus and Pierre Wibaux) an Army general (Phillip Sheridan) and a railroad magnate (James J. Hill). Other personal names, now rather pedestrian and unremembered, persist: Daniels County for local rancher, Mansfield Daniels, McCone County, named for an obscure Montana State legislator, George McCone and Phillips County for a former state senator Benjamin Phillips. Of Blaine County’s vastness, it is said that you can sit on your porch and watch your dog run away—for three days. It has the lowest population of all the counties at 0.274 persons per square mile. There are more antelope in Garfield County than there are residents, but Blaine and Garfield’s true name connections to Montana are still obscure. Liberty County, established in 1919, celebrated the patriotism that swept the land at the end of “The Great War.”

Then, of course, there are the innumerable counties that carry names of iconic landshapes associated with them. Glacier and Beaverhead are sound examples. Six counties have two word titles, but all the rest only have one word. One county celebrates a waterfall (Cascade) and another (Park) honors the nation’s first national park, even though most of the park is in Wyoming.

Other states, with less land mass than Montana, boast larger numbers of counties, like Kansas with its 105 counties and Iowa, with 99, all cut up into neat squares with little to distinguish one from another. In sheer numbers, Texas tops them all with 254. Chances are, Montana’s 56 will persist. It is unlikely that the state will consolidate some of its counties or expand with others. Our map is drawn up. Taken altogether, we like our county monikers. But who knows? We might appropriately end up with a county named Piegan or Rankin or Sacajawea or Absaroka.