Written by Suzanne Waring

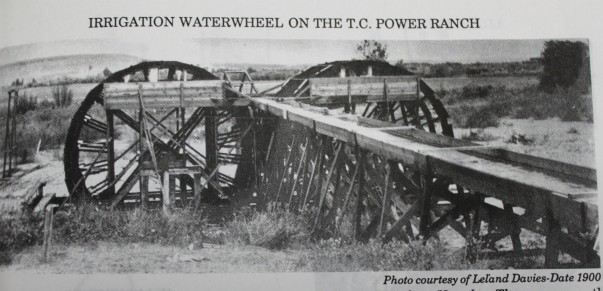

These waterwheels on the Sun River were offset and a flume channeled water to ditches. Photo taken from a history of the Sun River area and found at the Great Falls Genealogy Society, Montana Room of the Great Falls Public Library.

North Central Montana farmers began using water wheels as soon as they took up homesteads along the Teton, Marias, Sun, and Missouri Rivers before the turn of the 20th Century. Water wheels had been used in the Middle East, Asia, and Europe, especially by the Dutch, for eons, and the concept had migrated to the United States. It was only natural that those farming the bottom lands along Montana rivers on the eastern front of the Rocky Mountains would attempt to use water wheels for irrigation in a region where it rained only around fifteen inches a year.

The two major types of water wheels used in the United States were “overshot” and “undershot” wheels. Overshot wheels were built mainly for the purposes of milling grain and sawing wood and were powered with water that came from dammed mill ponds and entered from the top of the wheel forcing it downward into rotation.

Undershot water wheels were built for irrigation purposes and powered “underneath” by the current of the stream. As the current pushed the water against paddles or blades, it turned the wheel. Buckets at the outer rim of the wheel dipped into the stream on the underneath side and came up filled with water. The filled buckets came over the top of the wheel as it rotated and tipped enough so that the water poured into a flume that channeled the water into irrigation ditches below. Also called a “stream” wheel or a “current” wheel, these undershot wheels were not as efficient as the overshot wheels and more vulnerable to negative elements of streams since they were set directly into the river or into a channel dug next to the river, but they were simpler and cheaper to build.

As early as December 12, 1883, the Fort Benton River Press was anticipating the effect of undershot water wheels on the area: “If this system of irrigation proves successful, it will double the value of ranches in the bottoms along the Missouri, Teton, and Marias [Rivers] whereby reasons of cut banks and short bottoms it is impossible to get out a ditch without big expense for fluming.”

H. A. W. Jacobi was extremely successful in building water wheels on the Teton River. A May 11, 1925 Judith Basin County Press article indicated that the four water wheels positioned in a channel dug by Jacobi on the Teton River were designed to irrigate a thousand acres. The buckets on the rims of the wheels each held five gallons of water. When they ran 24 hours a day, seven days a week, they could produce an enormous amount of irrigation water.

A May 28, 1884 article in the River Press stated that one of the early water wheels on Mr. Rowe’s Ranch located on the Missouri River “has been in successful operation for the past two weeks and has been doing excellent work. It raises 400 gallons of water a minute, running a stream of 40 inches, miners’ measure, an ample supply to irrigate his large ranch.”

The “undershot” water wheel was efficient enough that it is said that, at one time, they dotted the banks of the Teton River. “The Teton River was especially conducive to water wheels because the banks weren’t too high, the river was fairly shallow, and the current was distinct but slower than that of the Missouri River,” said Steve Kelly whose family, including both the Kellys and the Stockings, has farmed and ranched on the lower Teton River for over a hundred years.

A Fort Benton River Press article on November 18, 1896, indicated that “Four wheels [on the Kelly Ranch], each having a capacity of 900 gallons per minute, will raise the water from the Teton to a height of about twelve feet, the moisture being distributed over some 200 acres by means of main and lateral ditches. About ten miles of ditch have been constructed and will be ready for work when occasion requires….The [water wheel] axles are made of iron castings, which give very little friction and increase the ease and speed of revolutions.”

Several who had farms on the Missouri River bottoms built water wheels between two barges that could be moved up and down the river to irrigate multiple fields. To prevent the water wheels being destroyed by ice jams or early spring floods, the farmers pulled the water wheels out of the river at the end of each growing season.

Once farmers saw that the water wheels were successful on the area rivers, water-wheel building became an industry for a number of carpenters in the area. They would take a crew and live at a ranch until the project was completed. When water wheels worked, they were a great addition to the tools used by the early farmer, but ice jams, floods, low-water seasons, and broken shafts from defective wood often left farmers discouraged with them. A History of Loma [Montana] indicated that the last water wheels to exist in the area were three on the lower Teton River. They were swept away by extremely high water in 1943. In time, loud, smelly—but more versatile—fuel-driven engines or electric motors replaced the romantic water wheels that sent out a creaking rhythmic sound that was loud enough to overshadow the sound of rippling water. The remains of many a broken and no-longer-used water wheel that fell into scrap piles strewn along the banks of the four rivers indicated that a new era for irrigating in North Central Montana had begun.