The Trail That Made Fort Benton Mercantile Owners Rich

Written by Suzanne Waring

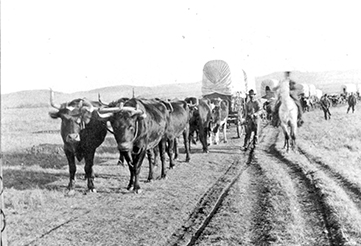

Early-day photo of one of the many oxen teams that transported tons of goods north to Southern Alberta. Whenever the ground became too rutted, the teams moved over and made a new trail. Photo from the Fort Benton Overholser Archives.

The Whoop-Up Trail connected Fort Benton, Montana, to what is known today as southern Alberta. When asked, many will wonder aloud whether the Whoop-Up Trail had something to do with prohibition and the illegal transportation of alcohol. Prohibition occurred from 1920 to 1933. The Whoop-Up Trail was used much earlier—in the late 1800s—when trade goods were shipped north to Canada.

Because of the Gold Rush in Montana, modes of transportation from the East to Fort Benton had already been established before the Whoop-Up Trail was used for commerce. In the years between 1860 and 1890, goods came to St. Louis or to Sioux City, Iowa, via rail. They were shipped by steamboat up the Missouri River and dispersed to Bannack, Last Chance Gulch, and other settlements.

By 1869, placer gold had mostly played out in Montana, and many prospectors had moved on to other possible gold-seeking opportunities. It was so quiet in Fort Benton that someone could shoot a gun down Main Street and not hit even a wagon.

There were two principal merchants in Fort Benton at the time. One was I. G. Baker who organized a mercantile business as early as 1866. His competition was T. C. Power. Fortunately, the next wave of business fell into place just when they both needed it.

In Canada, until 1869, the Hudson Bay Company had complete control of all of western Canada, what was known then as the Northwest Territories. When the Canadian government convinced the Crown of their desire to take control of the Northwest Territories’ land mass, the Hudson Bay Company, seeing minimal beaver pelt trade in the southern part of Western Canada, pulled out and left it lawless. The area was wide open to any kind of trade, including whiskey trade, until Canada could organize a system for governing.

Meanwhile south of the Canadian border, the Gold Rush had pushed the American Indians north of the Marias River. Buffalo hides were still being sought for coats and robes as well as for belts for industrial machinery. Traders followed the Indians north with the idea of continuing to trade goods for the hides.

In the late 1860s the United States had decided to enforce an old law which forbade the sale of liquor to Native Americans. At first, traders thought they would move into Canada and then smuggle intoxicants back into Montana. Once they got there, their plans changed. They found trade with the Canadian native people just as lucrative and beyond the reach of the American Cavalry.

I.G. Baker got into the action and sent company men, Johnny Healy and A. B. Hamilton, with whiskey and other goods across the border. They established in 1869 a fort at the confluence of St. Mary’s and the Belly River—now called the Oldman River—near where Lethbridge, Alberta, is located today. When the buffalo hides, that had been traded, were sold, Healy and Hamilton grossed $50,000. The original fort was damaged by fire that winter, so they built a permanent one within the year. In the beginning it was called Fort Hamilton, but later it earned the nickname of Fort Whoop Up.

Above: Modern replica of the Fort Whoop-Up interior yard near Lethbridge, Alberta.

Over forty forts were built in Alberta. Baker and Powers had several of the forts in southern Alberta in amongst those of free traders. Forts had names such as Robber’s Roost (Fort Kipp), Stand Off, Fort Spitzee, Cypress Hills, Fort Conrad, and Weatherwax’s Post.

Some say the reason the trail became known as the Whoop-Up Trail was because the bull train drivers used the word, “Whoop,” when they urged teams forward. Others say the Indians whooped it up after they bartered their buffalo hides for intoxicants. The most likely reason for the name of the trail and fort to begin being used was when a trader, Johnny LaMottee, responded with “They’re still whoopin’ ‘er up” when asked by John Power about trade activity at the fort in Canada.

To travel between the two forts, traders paralleled what was the less-defined Old North Trail which was a path east of the Rocky Mountains the Indians had used for years. Soon a better defined track, which was sometimes 50 feet across, was established from Fort Benton along the Teton River and then toward Shelby and northward to the Oldman River. They traveled across rolling prairie, avoiding coulees—and there were many—by taking the highroad wherever possible.

Although projection maps of the Whoop-Up Trail show that the trail outside of Fort Benton was located on the south side of the Teton River, undisturbed pastures on the north side of the river that have been utilized by seven generations of Steve Kelly’s family (going back to 1867) indicate that one of the trails used by the freighters was on the north side of the river.

“The gumbo soil on the south side of the river was called the ‘dry road’ because freighters used it when the soil was dry, but when wet, it was impassable, slimy mud. Then the freighters used what they called the ‘muddy road’ on the north side of the river because its sandy soil was more readily navigable during wet conditions and dried out faster. The south road was preferred when dry because the hard-packed gumbo made for faster traveling,” Kelly said.

Both dry roads and muddy roads were used in several places along the 240 miles between Fort Benton and Fort Whoop-up.

Between 1875 and 1877, I. G. Baker shipped 3,000,000 tons of goods and T. C. Power shipped 500,000 tons north by bull trains. Teams were normally made up of eight yoke of oxen but could be between six or twelve yoke. Most often three wagons were hooked together with the first one carrying the heavier cargo of around five tons; the second wagon carried around three tons; and the third, two tons. Trains of about eight to ten teams usually traveled 10 to 15 miles a day. The trip took 14 to 20 days. Goods of all types—including specially ordered dresses and hats—went north, and buffalo hides came south. During the summer it was reported that as many as a hundred teams could be on the road at the same time. Legitimate trade was profitable, but diluted whiskey was even more profitable.

Whiskey was one item that the Indians wanted in quantities, and that is what they got, but—as the folklore goes—it was diluted with unusual ingredients, such as India ink, gun powder, cayenne pepper, chewing tobacco, black molasses, and, of course, water. The Indians were satisfied with the diluted booze as long as it burned going down and had a “kick” to it.

The North West Mounted Police (NWMP) arrived in 1874 and put a measure of control to the whiskey trade. John D. Weatherwax, among a few others, didn’t get the word in time, was caught, and spent some time in a Canadian jail.

By 1880 buffalo herds had been killed off, but Baker had gotten the contract to supply the Canadian government with goods. In 1882 the NWMP was doing a half million dollars worth of business with Baker. The company also served as paymaster, had the mail contract, and offered a regularly scheduled stage pulled by horses from Fort Benton up the Whoop-Up Trail to Fort Whoop Up.

When the Canadian Pacific Railway arrived in 1883, the Whoop-Up Trail gradually lost out. The last bull train traversed it in 1892. Thirty years later, when prohibition was declared in the United States, the back roads of north central Montana, such as Bootlegger Trail, were used once again for illegal movement of intoxicants, but this time the goods moved south from Canada into the United States.

The author appreciates the research and writing done by the following individuals that made this article possible: • Berry, Gerald. Whoop-Up Trail: Early Days in Alberta…Montana (Occasional Paper No. 29). Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada: Applied Arts Products Ltd.1955. • Cushman, Dan. Old North Trail. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. 1966. • Kelly, Steve. Interview and tour of his pastures, March 11, 2015. • Lepley, John G. Birthplace of Montana. Missoula, Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company. Latest edition 2008. • Tolton, Gordon, Healy’s West: The Life and Times of John J. Healy, Mountain Press Publishing, 2014.